Processing vs Fresh Market Sweet Corn: A Plant Breeder’s Perspective

Planting season is winding down in Wisconsin, and there’s a lot of sweet corn in the ground! Many of those acres, especially in the Central Sands region, are for processing—canning or freezing—instead of the fresh market corn you’d see at a grocery store or a farmers’ market. At IFSI, we’ve been striving to continue growing in the processing sweet corn market in a big way. Last fall, the company finished its acquisition of the Del Monte sweet corn breeding program, which included germplasm focused on processing uses, rather than the fresh roadside or packing/shipping hybrids that make up the bulk of our portfolio. We’re already incorporating this Del Monte germplasm into our breeding pipeline – a wider base of genetic variation in a breeding program leads to more genetic gain, resulting in better hybrids being produced. Our newest processing hybrids will soon be making their way through our trials, and hopefully into a can of sweet corn. Food processing companies don’t buy just any sweet corn, cut the kernels off, and stick it in a can. Some hybrids work for processing, and some don’t – our goal is to provide hybrids that perform throughout the supply chain, from the grower’s field to the canning or freezing plant to the kitchen. This means paying attention to some specific traits that set processing sweet corn apart from fresh market hybrids.

Eric Brucker, one of our sweet corn breeders, wrote an article last spring talking about how all sweet corn isn’t the same. He has an excellent description of the handful of “sweet corn genes” that result in the accumulation of sugars rather than the starch we see in dent corn.

Different endosperm types in the same sweet corn inbred. Dent corn (Ia453-wt, left) has plump seeds and a high starch content. sh2 and su1 sweet corn (Ia452-sh2 and Ia453-su1, center and right) have higher sugar contents, and are both used in commercial processing. (Image adapted from Hu, Y., Colantonio, V., Müller, B.S.F. et al. Genome assembly and population genomic analysis provide insights into the evolution of modern sweet corn).

All sweet corn, whether used fresh or for processing, has one or more of these genes, but breeding for processing corn is different than breeding for fresh market sweet corn – specialized end-uses and unique customer preferences can change the traits we value the most and change the dealbreakers that we select against. The ideal processing type, with a larger ear, deep kernels, and a strong yellow color, is in the first image below, with a fresh market shipping hybrid for comparison.

Left: A processing hybrid, with deep kernels on a large ear

Right: A fresh market hybrid, with slender ears, refined kernels, and an attractive husk package

Fresh market vs processing types

In fresh market sweet corn, there are a lot of traits we need to be conscious of when going through a field trial, because we’re after the perfectly sized, flawless ears that people want to buy from their favorite roadside stand or grocery store. Characteristics like husk length and husk color that will visually appeal to the consumer are important, as well as having an ear size that can work for packing and shipping. Ears that are too long, too wide, or with too long of a shank don’t pack efficiently, cutting into yield and a grower’s income. Any of these are dealbreakers that will cause us to choose a different hybrid to advance in our trials. Kernel tenderness is also a big consideration; our highest quality IFSI Reserve hybrids have an extremely tender bite, which is acceptable because a lot of fresh market sweet corn is picked by hand. Fresh market shipping types are often less tender, to handle machine picking and packing options, but are still tender enough to have an excellent eating quality.

In a hybrid destined for the processing plant, exterior traits and visual appeal become less important, and those qualities get less weight when we make selections and decide which hybrids to advance in our trials. I’ll add a note here that traits like husk protection and tip fill, which need to be excellent in a fresh market hybrid, are still important in a processing hybrid. However, since kernels are usually cut off the cob in the processing plant, more variation is generally acceptable in sweet corn for canning, freezing, or other processing uses. In processing hybrids, yield – measured in cases of canned sweet corn per acre – is the key trait used in our decisions. In our internal trials, this means running all of our processing hybrids through our own small-scale processing lines, with our own husking machines and kernel cutters. This lets us look at a set of specific traits related to yield and suitability for commercial canning and freezing, and these are the traits that a grower or processing company will look at when testing out new hybrids.

Cases/Acre

Like bushels per acre in field corn, this measure of yield is the most important trait in a processing hybrid. Even a perfect husk package and consistently flawless tip fill won’t help if a hybrid doesn’t yield well. This is calculated from cut kernel weight – each case is around 13.5 pounds of cut kernels. For a hybrid that yields 740 cases/acre, that’s equivalent to 10,000 pounds of sweet corn per acre!

Tons/Acre

Another measure of yield – this is tons of green weight (unhusked corn right from the field). While this green weight doesn’t make it in the can directly, growers of processing sweet corn are often paid on basis of green weight.

Kernel Recovery

A processing specific trait, recovery measures the fraction of green weight that will actually end up as kernels being sold in a can. Recovery is usually expressed as a percentage – if a hybrid has a kernel recovery of 50%, then 50% of the green weight is kernels that get cut off the cob, and the remainder is husk, cob, and other waste. One reason we breed for ear shape is because it affects this trait in particular; the canning line’s cutting blades can’t cut as close to the cob on oval or curved ear shapes, resulting in more waste.

Bear paw shapes won’t go through a processing line and are selected against.

Kernel Depth

Simply the distance from the cob/cut line to the top of the kernel, kernel depth is less important in fresh market hybrids. For processors, more kernel depth (at least 13-14 mm) typically means more kernel mass per ear and a higher kernel recovery, so more cases per acre. A kernel that’s too shallow is also tough to cut from the cob.

Ear Diameter

While it’s relevant to fresh markets as well, processing companies often have very tight specs for ear size. This usually relates to how the ear moves through the processing equipment, and ears that are too short, too long, or too big around can cause machine blockages and poor kernel recovery.

Processing Agronomics

Outside of the yield- and ear-related traits, successful hybrids will have a suite of useful agronomic traits necessary in the sweet corn processing industry, where profit margins can be tight. For example, the return per acre for a fungicide application is lower in processing sweet corn relative to fresh markets, so planting a resistant hybrid to control diseases like Northern corn leaf blight and common rust becomes more favorable. Growers will also increase plant populations to increase yield and profitability, so density-tolerant hybrids are selected in our breeding pipelines. Furthermore, since all processing sweet corn is machine harvested, we also select more strongly against any hybrids susceptible to lodging or green snap. We can also look at multiple seasons of processing trials to get yield comparisons for our test and commercial hybrids in a way that isn’t as easy to do in fresh market trials. Unlike subjectively rated traits like husk and kernel appearance, which are rated on ordinal scales, processing traits like cases per acre and kernel recovery are very objective, and on a quantitative scale. As someone who likes having hard numbers, I appreciate that the data we get in our processing trials lends itself to more of the “precision ag” mindset.

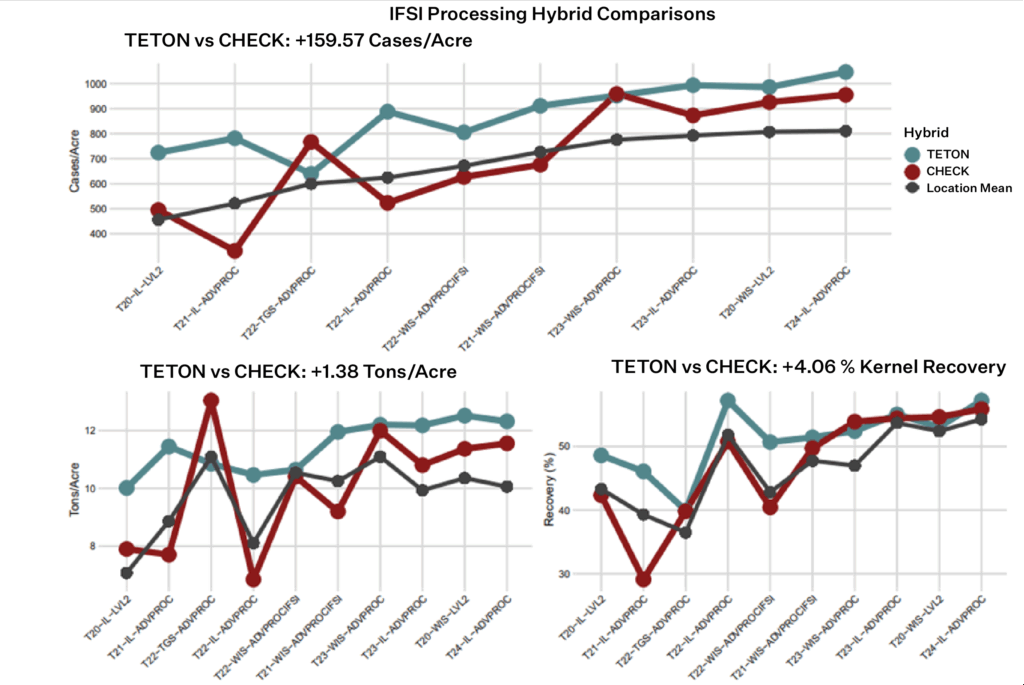

A head-to-head comparison of our processing metrics between two hybrids; yield and recovery can easily be compared between multiple trial locations in order to make the best hybrid choice.

At the end of the day, breeding sweet corn for the specifics of canning, freezing, and other processing requires some additional trials compared to our fresh market trials, and the data looks a little different. For a processing hybrid, we need to think about things like cases per acre, kernel recovery, and kernel depth, rather than flag leaf, husk, or kernel appearance. Still, the results are the same—we use those numbers to get better performing varieties for growers in the field, processors at the plant, and ultimately consumers at the table.